"A clearing in the woods is an archetypal American landscape that came into common use in the 18th and 19th centuries... The clearing gives a sense of protection. You are closed off, at least visually, from intruders. This provides a sense of seclusion and comfort..."

James Golden, The View from Federal Twist, pg 31

There is a world-famous garden in New Jersey just up the river from where my ever-so-great-grandfather Andrew Rose fought alongside George Washington on the shores of the Delaware. Around 1800, Andrew left that part of New Jersey with his wife and children to found the small town where I now live and garden in northwestern Pennsylvania. So it's with a fond personal connection to these woods and hills that I introduce you to the "clearing in the woods" that is now Federal Twist.

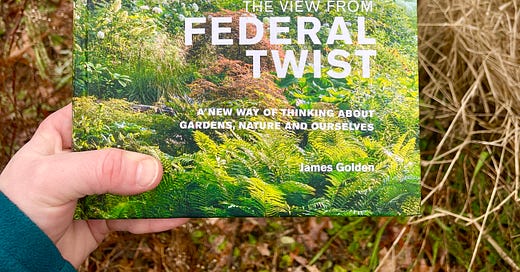

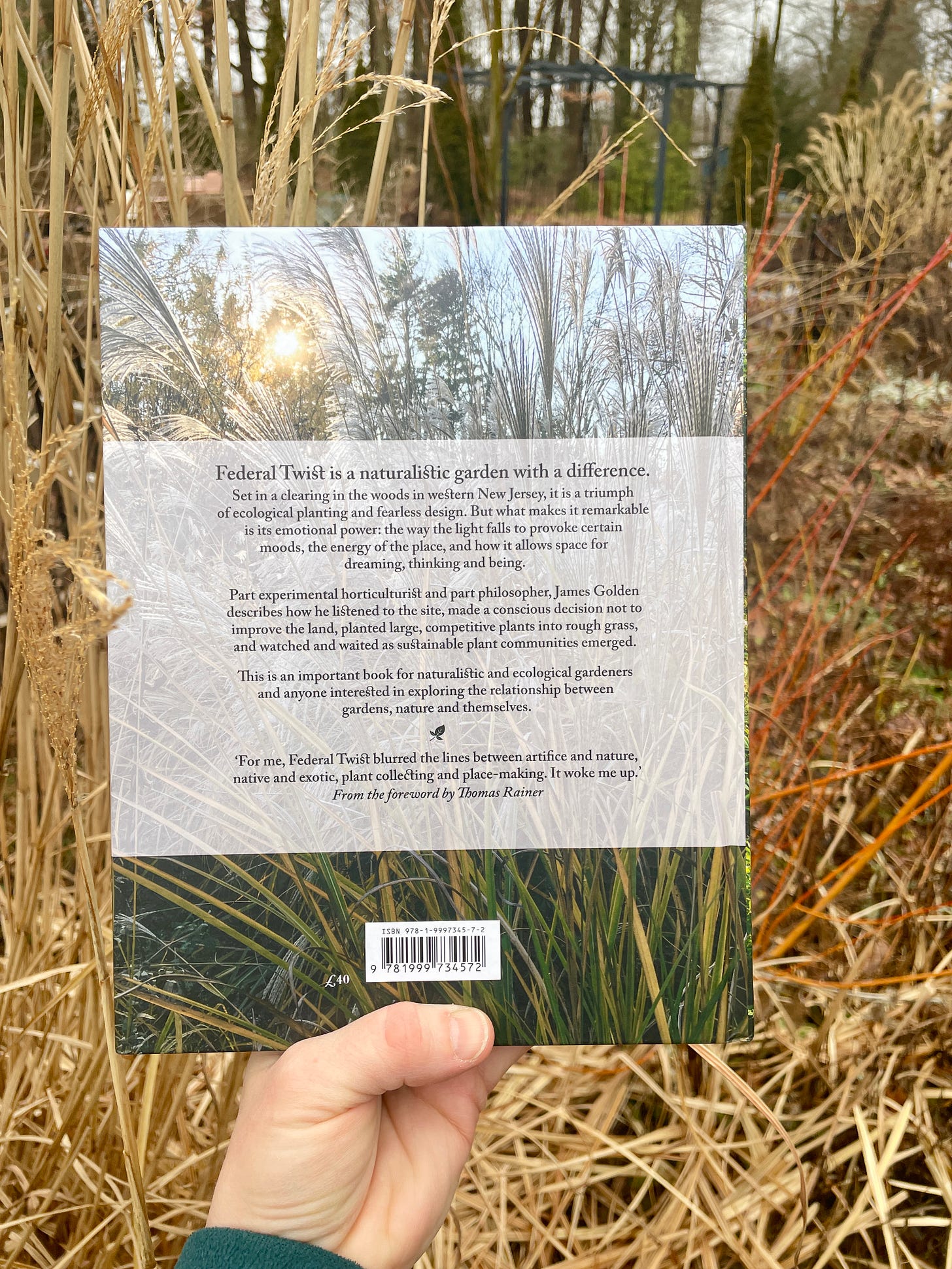

James Golden is the owner of the house and garden known as Federal Twist, and author of the popular book, The View from Federal Twist. It is published by Filbert Press, who says of James:

“James Golden lived in New York City for most of his adult life but nearing retirement, he followed a long-buried urge toward the natural world and moved to western New Jersey to make a garden. Fifteen years on, James is a celebrated garden-maker and thinker whose garden has featured in numerous publications and in his blog. In 2019 Monty Don visited Federal Twist for the BBC Gardener’s World series American Gardens.”

I’m thrilled to have James here today to talk more about his book and garden!

"I came to gardening late, when I started thinking about retirement — not as some practical way to keep myself busy, but in a much more thoughtful and intentional way. I asked myself where I wanted to be in the world, and I wasn't thinking about physical place. My meaning was far more metaphysical. I wanted to live in a garden, live a garden, in fact, to be a garden. Could I ask for more?" pg 14

Julie: You say in the preface that your garden is a place that holds you, where you feel "a part of the landscape... comforted, and a sense of belonging." Was Federal Twist made out of a desire to create safety? How have these comforting feelings grown for you in your garden? Was it planting the plants? Walking the paths year after year? Knowing the way the water sits in your garden, etc?

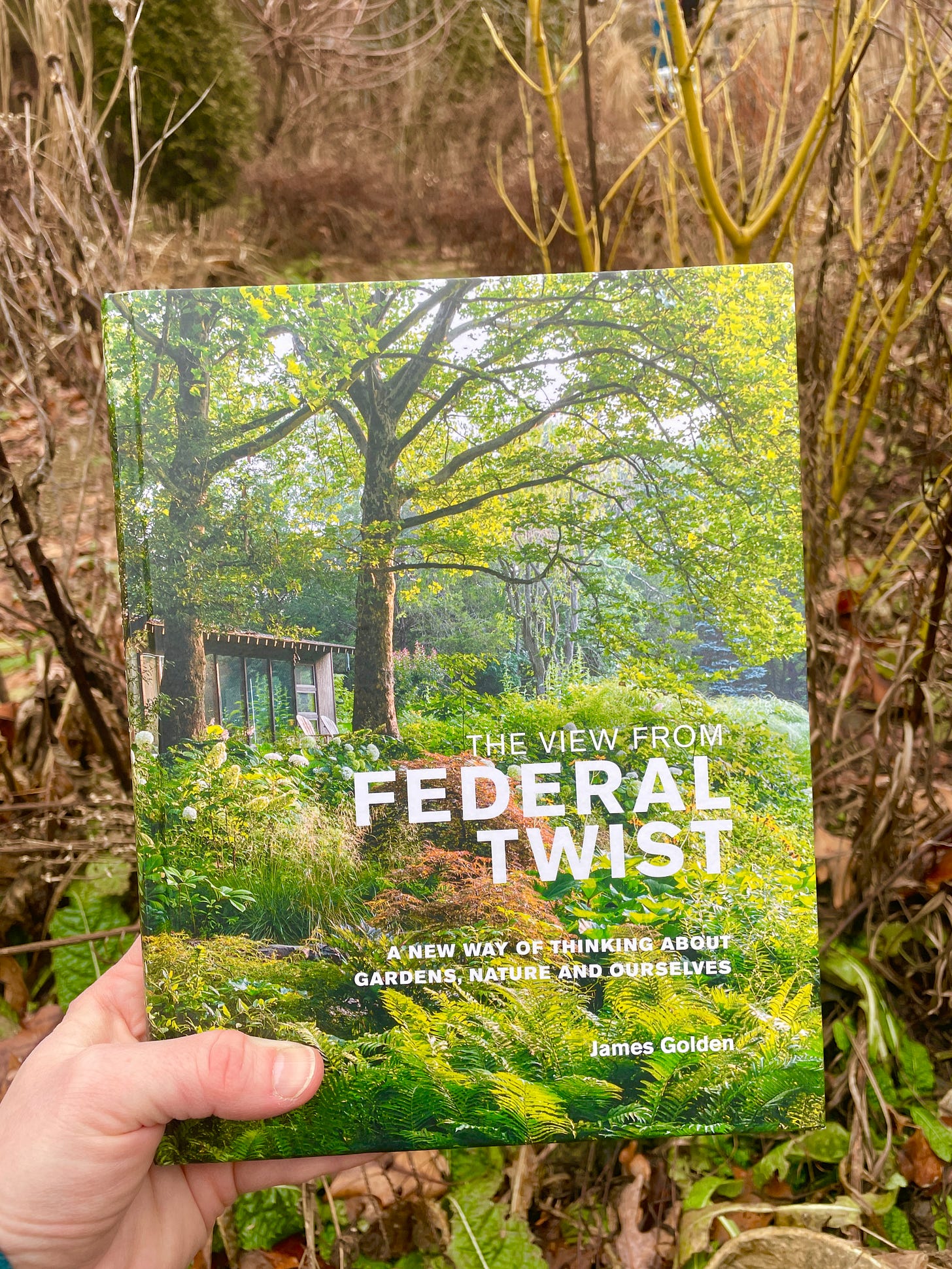

James: Feeling safe is certainly a part of it. But I think I need to explain what I mean when I write I wanted to “live in” a garden, to “live” a garden, to “be” a garden. On the face of it, this sounds a bit absurd. Part of this has to do with the kind of house I live in, and with its location as a prominent part of the garden—surrounded by garden. Built in 1965, the house is a mid-century style, with long, low lines, a wall of floor-to-ceiling windows facing southeast and many sliding glass doors, so there’s a view into the garden in almost every direction. When I get up each morning, I look out that wall of windows and sit to have a cup of coffee in my big green chair. Because the house is surrounded by garden, and because the garden is immersive, with many large, tall plants, when I step out, in any direction, I’m in the garden, looking at garden.

Through this constant and mutual exposure, I’ve come to feel at one with the garden. It occupies my thoughts every day. I’ve come to feel it’s really no exaggeration to say that I want to “live in” a garden, to “be” a garden. And in a very practical sense, that is so. The garden would not exist without me; it is an immersive garden you can get lost in because I want it to be like that; it looks wild because that reflects the look of the surrounding landscape, and something of my way of thinking about the world and how I wish it to be. And when I cease to exist, so will the garden. Something completely different will replace it.

"I was quite taken with that rather magical idea of this house set amid a garden, and I decided to accept it all— the good with the bad. It led me to create a garden totally different than anything I'd imagined." pg 24

"By accepting what was given—neglected woods, weeds, heavy clay soil, and too much water—I was agreeing to make a garden that was informal, naturalistic, ecological, melancholy at times, mysterious, a bit chaotic, wandering rather than direct, probably with many curves and few straight lines. I also was agreeing to limit myself to a plant palette dictated by the difficult soil." pg 47

Julie: I talk about a radical acceptance of our difficult growing conditions in my Botanical Opportunities class, and about how it can lead to a more interesting garden. Your book describes your own process of acceptance at Federal Twist. How has this acceptance made your garden more interesting? Is there anything that still feels hard to accept at FT? What are you unexpectedly grateful for at FT that was at first difficult to accept?

James: I suppose I’ll always have some regret that my heavy, wet clay soil prevents my growing many plants I’d like to see in the garden. I’ve always wished to have an area with many small-flowered dahlias growing amid grasses, but that will never be. Dahlias would never survive my conditions. But such limitations have forced me to seek out other sources of satisfaction beyond the merely pretty. Instead, I discovered the pleasures of an immersive garden with plants so tall visitors often get lost as they walk along the many curving, wandering paths. Being lost, feeling cut off, having to pause and think about the way forward, enriches the experience of the garden. The intent is to slightly disrupt your normal connection with the everyday world, to break a circling thought, to interrupt a worry, to give you the opportunity to hear a bee buzzing in a flower. To pull your attention into the present, to give you an encounter with the garden, its plants, its spaces, changing moods and lighting conditions. At such times, the garden can become imbued with meaning, emotion, and strong feeling. It can suggest the mysterious, the ineffable, the unknowable.

"'What exists' was an awful site for a traditional garden; most people would have seen the constraints of the site as reason enough not even to try. However, so much land in our world has been used and abandoned, left wasted, I wanted to use it as found, not to change its essential character, but simply to help it be a better version of itself. I believe that by paying attention, and taking appropriate action, you can make a garden almost anywhere." pg 53

Julie: What role does paying attention play when creating a garden in a difficult location?

James: It’s essential. You can’t make a garden (or do much else) without paying close attention to all aspects of the environment and to yourself.

Because I didn’t have models or guides to use, I was forced to pay attention—to experiment, to learn what worked and what didn’t work. I had no formal horticultural training, but I was an avid reader of books about gardens, so I did bring quite a bit of “book knowledge” to the project. For example, I remembered reading in one of Noel Kingsbury’s early books a section titled “Planting directly into rough grass.” Noel said this approach could result in a rough prairie, which I realized was my aim. But this was only a concept. I had to learn what plants could survive, even thrive, in my heavy, wet clay soil. So I bought plants I thought would match my woodland-edge ecology, planted them pretty much at random. (At this stage I gave no thought to design; I simply needed to learn what plants I could grow. I needed to find plants adapted to my ecological conditions.)

As the years passed, I did of course give thought to how the garden would fit its place. I thought about design, specifically about how to design a clearing in the woods, how to visually unify the garden with the house and with the surrounding woodlands. At the time, I don’t believe I’d read about Rachael and Stephen Kaplan’s theory of the importance of mystery, complexity, legibility and coherence but, once I found it, I felt it was something I had always known intuitively, and it was and remains a constant way of ‘seeing’ and understanding for me.

Julie: You mention many times in your book that you used observation, experimentation, and being responsive to conditions to create Federal Twist. What do you think was your biggest motivator towards a slower "wait and see" approach? Was it partly financial constraints that slowed the process? Was it the overwhelmingness of the task? Or perhaps it was just savoring and enjoying the process as a creative endeavor?

James: Cost was certainly a factor. Our house is in an area with a huge deer population, so I understood I would need to enclose the garden, regardless of placement or dimensions, inside a deer exclusion … an expensive proposition. Once I understood the nature of my soil, if cost were no object, I probably would have brought in many truckloads of better soil if I could have afforded that, improved the drainage, perhaps added a lot of rock, added landforms to create drier and wetter areas. I say probably, because I also was enticed by the idea of working with my existing conditions, letting the nature of the place lead me. And that’s what I ultimately did. I realized the struggle with the apparently unwelcoming place could become a creative endeavor. (Yes, we did put in a deer exclusion.) So yes, I learned to savor and enjoy the process, but I have to admit it has always been a struggle too.

"This I learned quickly: in highly competitive conditions, only large, well-established plants are likely to survive the stress of the first few years; small plants will probably be overwhelmed. So I planted large, competitive species directly into the existing grass and weeds, using the vegetative cover to maintain stability, until the new plants could form communities and dominate the space. Eventually, I discovered that many of the species able to thrive in the conditions on the site were prairie plants native to the American midwest, some were highly effective exotics, and others were locally native, even indigenous to the site." pg 58

Julie: You mention so many in your book, but what are a few of your favorite plants that grow and thrive in the wet clay at Federal Twist?

James: It’s an oversimplification to describe my garden in this way, but useful to quickly convey a visual impression. So I suggest you visualize the garden as a mass of undulating grasses, mostly large and round in shape, marked by a scattering of very tall, rather narrow emergent (vertical, spear-like) plants that quickly grow, gaining a height of six to ten feet and flowering in July. In autumn and winter, the tall emergents turn brown, then almost black, creating a powerfully graphic scene that lasts well into winter. I use some plants almost as sculpture.

I’m probably exaggerating a bit to give you a simple visual impression of the garden. The planting is actually much more complex than this description implies; there are probably well over 300 different species of plants adding to the visual diversity.

My favorites among these massive plants are Miscanthus of various kinds, three tall mid-western American prairie plants: Cup Plant (Silphium perfoliatum), Compass plant (Silphum laciniatum), and Prairie Dock (Silphium terebinthinaceum), and the tallest plant of all, Inula racemosa ‘Sonnerspeer’, a giant Elcampene that has origins around the Himalayas. It has large floppy leaves in summer, and grows as high as twelve or thirteen feet, though it diminishes in height as it ages; its strong woody structure keeps the plant erect through all kinds of weather, even strong winter winds in rain and snow. In late autumn and winter, it turns black and becomes like sculpture, with strong verticals resembling specters marching across the landscape.

I first read about this Inula in the catalogue of a small nursery (Blue Stem) in British Columbia. The nursery wrote that Wolfgang Oehme had used the plant after coming to America from the former East Germany. After Oehme met Jim van Sweden, they formed Oehme, van Sweden & Associates, the landscape architecture firm that introduced what quickly became known as “The New American Garden,” a style of gardening that used large sweeps of grasses and perennials to create and popularize a much more naturalistic landscape. I was intrigued by Oehme’s use of unusual plants and just had to try this one, so I ordered two from Blue Stem. They grew very quickly and well in my heavy clay and seeded about, giving me far more plants than I could use. I learned to deal with them by removing seedlings, and this plant has become one I would not be without.

"Early on I could see the need for more structure to contain the feeling of wildness and to indicate intentionality. Among Americans in particular, with their national fixation on the neat, suburban front lawn, the 'fear of the wild'...can be an obstacle to acceptance of 'looser' styles... Use of 'orderly frames' is one method to make such gardens more visually accessible to people unfamiliar with the look of natural landscapes. I had been practicing a variation of this 'framing' concept by using paths, stone walls, and other features..." pg 89

Julie: What do you think has been the most effective element to "orderly frame" your garden-in-a-forest? Do you have a favorite spot at FT?

James: The people who built the house in 1965 created a little hill (only about 12 feet tall) and built the house on it to keep it above the surrounding very wet land. Outside the house, now overlooking the garden, is a gravel terrace that wraps around the house, making an elevated place from which to view the garden. The little hill feels like the center of the garden (although it isn’t, geometrically speaking), with three tall London Planes rising from it. This central mass of large trees ‘speaks’ to the large wild trees in the woods across the garden.

I think the terrace is my favorite place in the garden. This raised viewpoint is one aspect of the orderly frame that ‘controls’ the view of the garden. Other important framing elements become visible when you descend from the terrace into the garden below where several hundred feet of native stone walls and many winding, intersecting gravel paths act as framing elements. You have to walk the paths to recognize this framing role, and to understand how the framing elements can be irregular and curving. This is especially visible from above.

"I took making a garden extremely seriously, almost as if it were a life or death proposition. Perhaps this was owing to my increased awareness of mortality. My mother and my only sister died during the making of the garden, leaving me alone, the last of my line, and I was nearing retirement age even as I started the garden. So garden-making, though a source of happiness, excitement, and great joy, was always touched with melancholy... Melancholy is a rich and complex emotion." pg 229

Julie: This kind of intensity in garden making sounds so familiar to me, though it happened at the opposite end of my life. As a 25-year-old dealing with miscarriage, I felt that death surrounded me. Gardening gave me a way to surround myself with life instead. It gave my mind a creative outlet to work towards a sort of harmony in the physical world. Especially during times of grief, the garden has been an important outlet for me. How is emotion carried in the garden?

James: Melancholy can be a troubling word. But it means far more than depressing or sad. In literature and music, it can describe tremendous depth of feeling. The word is also closely related to nostalgia, and can carry a garden, and a garden visitor, into hard-to-define emotional realms. I often think of American paintings of the Hudson River School or German Romantic painters such as Caspar David Friedrich as exemplars of this kind of melancholy.

I also think the word is closely related to mystery. I want my garden to be a place where a visitor can explore all kinds of feelings, and I believe, among them, melancholy and nostalgia are important parts of life in the garden.

Julie: Unlike some other forms of art, gardens are not static things but change throughout the seasons and years. I have a space we call the "cottage garden" at Havenwood that is a successful space as far as the design of the hedges and paths, but the planting needs a total redo. Not only does the planting need to be weeded and divided but my tastes have changed since I first planted it a decade ago. I dream about ripping out some things and starting over.

From your Instagram account it seems that a sort of "second draft" is happening on parts of Federal Twist these days as well? What is the biggest change you have made to your garden in the last couple of years?

James: My garden is always changing. If you’ve read the work of master French landscape architect Gilles Clement, you will recognize my garden is a garden he refers to as ‘jardin en movement’, or garden in movement. I recommend Clement to your readers.

Most recently, since last autumn, I’ve been making major changes, removing many large Miscanthus from the garden and clearing areas for new plantings this spring. While I do not intend to change the overall look of the garden, I do want to introduce other grasses with different shapes, textures, and seedheads. I also want to experiment with some other herbaceous perennials that, I hope, will succeed in wet clay, among them different Amsonias. (Mt. Cuba Center recently released a report on a 12-year trial of native Amsonias). I’m interested, too, in expanding use of shrubs in the garden. This will be the most extensive planting change I’ve made since the garden began. I should also tell you that, as I age, I realize I need to simplify care and maintenance of the garden, and that is the reason for the changes I will make going forward.

"Can a garden still be redemptive, transformative? Can it bring place and meaning together?"

The View from Federal Twist, pg 69

"Can the garden 'do' something to change us? I sit in my green chair, thinking such a thing is possible... you give up your goals and just listen; perhaps you see something you didn't notice before. You learn to let the garden be the protagonist. This is humility, allowing the 'other' to take precedence, perhaps seeing the garden as a symbol of something larger and much more important."

The View from Federal Twist, pg 229

What a rich feast today. Thank you for joining us here today, James!

I know that many readers here will want to take a look at James’ book, The View from Federal Twist, by Filbert Press.

You can read more updates from James Golden on his garden blog, View from Federal Twist. (This is how I found James and his adventures at FT over a decade ago - recommended!) Or find out more about his design practice www.federaltwistdesign.org

Find James on Instagram: @ImFederalTwist

How has James Golden inspired you today? Love to hear!

*Amazon Affiliate links are included in this newsletter. I make a few cents per recommendation, each of which I hope will be helpful to you!

Note: I also include many links (which are not affiliates) to other sites to aid your research and photo credit purposes.